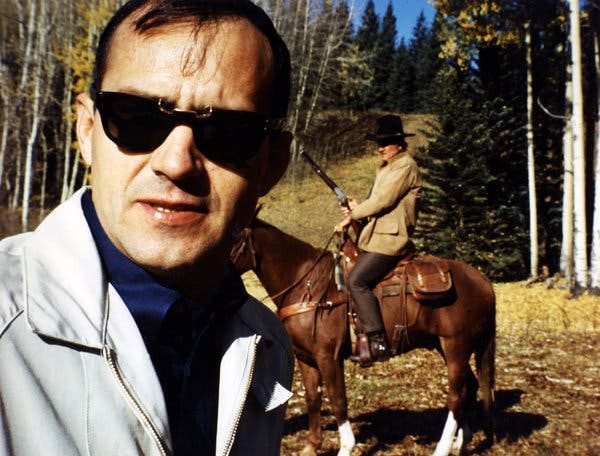

Charles Portis with John Wayne as Rooster Cogburn, on the set of “True Grit,” 1969

My favorite writer died today - his name was Charles Portis, and he was 86 years old, and had been in failing health for some time. I didn’t like seeing his body of work widely celebrated on this sad day. Why? It’s very simple - I want it all to myself.

I’m greedy, when it comes to Portis’s writing. I want the journalism belatedly and superbly collected and published in 2012 to fly under the radar, just like the man himself. I want Charles Portis’s five novels to remain a secret I only share with close friends who I think deserve it. I do not want to hear somebody read him and just liked it, thought it was fine - thought Norwood or True Grit or Dog of the South or Masters of Atlantis or Gringos was okay. No. That’s not the appropriate reaction, it was wasted on you, and I am just a little more disappointed in humanity than I was a minute ago.

See, here’s the thing. I believe he was the best fucking writer in America. Period. I don’t want to hear a word otherwise. As much as he avoided any publicity, avoided any high-level scrutiny - in years of obsession, I’ve found only two or three interviews with the man, only one of them at all revelatory - he won’t escape that in my mind.

Your standard member of the literary pantheon typically devotes their career to what the critic Dan Schneider calls an “artistic striptease.” I won’t name names, but like pornography, you’ll know it when you see it. On their way to the canon, such writers preen, they show off, they essentially try to impress upon the reader that the author is smarter than them. Elmore Leonard’s rule of writing - “Never use a verb other than ‘said’ to carry dialogue” - is anathema to this fictive mode.

I don’t have an explanation for this, except it probably feels pretty good being rich and successful and considered brilliant, certainly more brilliant than one’s readers. If this sounds reductive or unkind, too bad, because I think Schneider, a crank on some subjects, gets this phenomenon exactly right:

“…Art is communication, clarified and at a higher level than normal. But, to do so would require real hard work, real talent, and not the easy out of artistic striptease. The plain truth is the reason that these PoMo frauds and charlatans do such is because they know that their bodies, if revealed, would be blubbery, cellulite ridden hulks, rather than taut. Lean, sexy works of profundity and grace.”

Here, we have hints of the alternative: that of the craftsman. The professional. The professional writer doesn’t bask in this cheap heat; they’d feel embarrassed, crawling out of their skin with discomfort. They can’t go to whatever stupid parties the villagers of Manhattan are throwing, because they are working. And what they are working at is the precise opposite of puffing yourself up into a literary aesthete.

A friend of mine once explained it this way. Mark Twain - who shares a number of personal and professional traits with Portis - excelled in a style alien to the kind of writers Edgar Allan Poe termed “The Frogpondians.” That style was not to make oneself prove superior to the reader, with no actual strength behind the posturing. If David Foster Wallace (I had to pick an example, and his work deserves it) conveyed banal and uninteresting ideas, without skill in the fundamentals of storytelling, and with no human intelligence - all in an exceedingly labyrinthine form, explicitly designed to herald his own brilliance - Twain conveyed complex ideas simply, in the language of his fellows.

You tell me which is harder to do. If you answer incorrectly, I’ll simply point out “Huck Finn” will still be read in five-hundred years, if the Earth still exists. Huck and Jim’s voyage on the river will be remembered with the same level of emotive possibility it conjures now, one-hundred and thirty-five years after publication.

I’ll insert one quick example of just what such writing can convey: Huck’s realization that “The Duke and the Dauphin,” royal pretenders who travel the river, fleecing the credulous locals, are con-men. Twain surprises us:

“It didn’t take me long to make up my mind that these liars warn’t no kings nor dukes at all, but just low-down humbugs and frauds. But I never said nothing, never let on; kept it to myself; it’s the best way; then you don’t have no quarrels, and don’t get into no trouble. If they wanted us to call them kings and dukes, I hadn’t no objections, ’long as it would keep peace in the family; and it warn’t no use to tell Jim, so I didn’t tell him. If I never learnt nothing else out of pap, I learnt that the best way to get along with his kind of people is to let them have their own way.”

Of course, Huck realizing these two he’s sharing a raft with are grifters is notable. But what does Huck do with the information? A writer with a less sure sense of Huck Finn might fixate on the dilemma. But to Twain, it’s obvious what Huck does: Nothing. It’s none of Huck’s business, he doesn’t even want to upset good Jim with it. We get a sense of Huck’s sense of the world, of what would be right for him to do, and what would be wrong. We have a better sense of his character than when we started reading the paragraph. Best of all, it’s funny, and convincingly written as Huck, were he a real person, would be saying it.

The river is deep here. In a few short sentences, we see how the upbringing of this character molded him. And it’s not fantastical. The realization, the decision, the action here is all entirely plausible, speaking to Twain’s good sense of people - a skill I think is indispensable to writing, but which can’t be taught, only learned.

A wise man explained to me that the tribes of early humanity probably included somebody who would be their storyteller. They’d all sit around the campfire and someone - let’s call this guy “Ugg” - would recount that sabre-tooth tiger old Grok fought, bare-handed. Maybe their pal Tok would start daubing the cave-walls with berry juice and mud, depicting those wooly mammoths they hunted. Maybe Ugg would start memorizing the best stories, maybe written language would develop, and so on and so forth.

What a gift to give your fellow human beings!

Next time: Let’s talk about why Charles Portis was, for me, better than anyone else in America in answering this calling.

You gave Francis True Grit for his birthday when he was about ten. Michael and I took turns reading it out loud to him, the three of us lying together in his bed. We talked about the book by day and we couldn't wait to get back to the story each night. We LOVED it! And of course we watched the movie when we finished the book, not wanting to leave those characters. Thank you for the book, for the experience of reading it together, and for the memory of it now. Thanks, Daniel. Thanks, Charles Portis. RIP indeed.

Was waiting to hear from you on this. it was your recommendation of Dog of the South that got me reading him.